Information Chaos and Electronic Medical Records

photo by: dM.nyc

Before I developed software I was a clinician, a prosthetist. My job was to problem solve for 8-13 patients a day. In order to make decisions, I needed to understand the patient I was caring for. Patients’ medical records should have given me a clear, complete, correct, and concise image of who the patient was; they didn’t. I was overly dependent on the patient giving me their story and I was not able to trust the medical record. Too much of the medical record was, as described by John Beasley, “information chaos.”

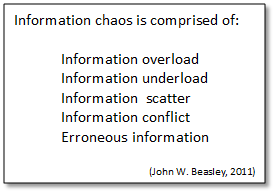

It was 2011 when Beasley et. al. published ‘Information Chaos in Primary Care: Implications for Physician Performance and Patient Safety’. I’ve read and referred back to the article many times. In it they described information chaos in electronic medical records as being “comprised of: information overload, information underload, information scatter, information conflict, and erroneous information”. Beasley also described how all our decisions are made based on our understanding of the situation. ‘Situational awareness’ is the catch phrase they used. The better the decision maker’s ‘situational awareness’, the more likely a correct decision is made. The information chaos within the medical record can be overcome, situational awareness improved, and decision quality improved if the clinician has enough time to mitigate the information chaos. But we don’t have the time, ironically, because the same electronic medical record, the tool meant to save time, takes up too much of our time.

By giving you some insight into my previous experience, I hope to help you understand information chaos in medical records and its’ impact on our decision making and patient care.

In my clinical practice I relied on and read the notes for patients referred to me. Each note was 8-12 pages long [information overload], and often I needed to search more than one note in order to uncover the pertinent content [information scatter]. That’s a lot of reading.

These long electronic patient records are cluttered with templated sections, cut-and-paste from previous notes, structured data in problem lists and medication lists, and narrative prose [information overload]. The narrative prose were the most helpful to me. These narrative sections were never found in the same location but would often be interspersed throughout the note [information scatter].

Every clinician structured their notes differently and clinicians were inconsistent in their note structure from note to note. I had to devise strategies for searching through the pages to find the narrative prose. Usually narratives were towards the end, but not always [information scatter], and so the entire note had to be searched for fear I would miss a critical piece of information the clinician meant to convey. This was a less than entertaining version of the children’s game, “Where’s Waldo?”.

Every clinician structured their notes differently and clinicians were inconsistent in their note structure from note to note. I had to devise strategies for searching through the pages to find the narrative prose. Usually narratives were towards the end, but not always [information scatter], and so the entire note had to be searched for fear I would miss a critical piece of information the clinician meant to convey. This was a less than entertaining version of the children’s game, “Where’s Waldo?”.

My strategy was to first look for a change in font and spacing, just like this section of the essay, and then search the note for the matching sections, composed in the same font.

If a font change did not help me identify the composed narrative prose, I looked for speling erorrs, incorrect punctuation;, repeated words word, incorrect spacing between words , and poor grammar. If the note was pretty, with none of these errors, that was not good. It took too long to find what I needed in pretty notes, when they were consistent in appearance through all 12 pages. Pretty notes were also unreliable because they were frequently entirely from a template.

Templated sections of notes were the prettiest, and the most unreliable section of the note. The templated sections of the note often, often, stated that the patient had “5/5 strength and complete range of motion in all joints…sound gait and stance”, even though the patient came into the office in a wheelchair and had been referred by the note’s author for a leg brace because one side of their body was partially paralyzed, or they needed a prosthesis because a limb was amputated [erroneous information]. Templated sections of notes were typically not corrected to reflect the patient. Adding to my frustration, no mention of the patient’s need for an orthosis or prosthesis would be found in the narrative sections of these same notes, even though the patient had been referred to us for an orthosis or prosthesis during the encounter documented in the note [information underload]. Perhaps this occurred because the notes were sometimes generated days after the encounter and the clinician may not have remembered making the referral?!

Cut-and-paste sections of notes usually contained font inconsistencies as well as spelling and grammar errors; therefore, I could not always be sure the unpretty sections of a note were original content and narrative from that particular patient encounter, or if they were cut and pasted from a previous note. The big problem with cut-and-paste was that errors from previous notes were sometimes passed through the record, from note to note, without being corrected. For example, many times we received notes with a mention that the patient was diabetic. You would find these had been carried through in cut-and-paste sections; yet, the patient would emphatically deny they were diabetic [erroneous information]. The problem list might also state these non-diabetics were diabetic, or it may not [information conflict]. It seemed the cut-and-paste segments were not being read before they were cut and pasted in.

If you referred patients to me I assure you, you weren’t the only one who made these mistakes, it was more the norm than the exception. I had two full time staff dedicated to calling doctors and requesting they amend and correct their notes as we could not treat a patient without proper documentation supporting the need for our services.

Electronic medical records were perceived as the panacea in 2009 when the HITECH act, with its’ incredibly successful carrot and stick motivations for the adoption of EMRs, was signed into law. Since then, healthcare productivity has steadily declined and the costs have soared from $2.5Trillion (2009) to $3.6Trillion (2019 pre-COVID). EMRs brought us more and more information chaos, which contributed significantly to this decline. Be careful what you wish for.

Computers can greatly improve productivity and in doing so reduce costs–just as we all dreamed they would. We all, in healthcare, know we need to eliminate information chaos and make the patient’s record actually represent who the patient is. Massive amounts of time would be saved, we would make better decisions, outcomes would improve, lives would be saved, and the cost of healthcare would be reduced. Identifying a problem is not solving the problem, but it is a start.

What other examples of information chaos you have seen?

Eliminating information chaos is at the core mission of our startup.